Our Flooding Problems

South Holland can flood in any season. Floods have been caused by localized storms, rain over several days on saturated ground, and snow melt. Properties in South Holland’s floodplains are subject to three flood problems: overbank flooding, drainage problems, and leaky or obstructed storm sewers.

Overbank flooding

South Holland is subject to overbank flooding from three sources:

– The Little Calumet River flows through the center of the Village, from east to west. The Little Calumet River drains northeastern Illinois and northwestern Indiana via several tributaries. At South Holland, the river’s watershed is over 200 square miles. A small tributary, Thorn Ditch, drains the central part of South Holland. Its overbank flooding is caused by backwater from the Little Calumet River.

– Thorn Creek flows from the south and joins the Little Calumet River on the southeast side of town. Thorn Creek collects water from Deer, North, and Butterfield Creeks and Lansing Ditch. The Thorn Creek basin drains over 100 square miles, accounting for over half of the water that enters the Little Calumet River at South Holland.

– The third stream is the Calumet Union Drainage Ditch, a man-made ditch that drains 18 square miles of the Markham and Harvey areas to the west. It joins the Little Calumet River in the west part of the Village.

Most of the Village’s overbank flood problem is in the Little Calumet River’s floodplain. Because the area is so flat, the flooding of one stream is accompanied by flooding on the other two.

When these streams become overloaded, water leaves their banks and flood neighboring properties. Overbank flooding has occurred on an average of every three years. It was bad enough in 1990 and 1996 to result in state and/or federal disaster declarations.

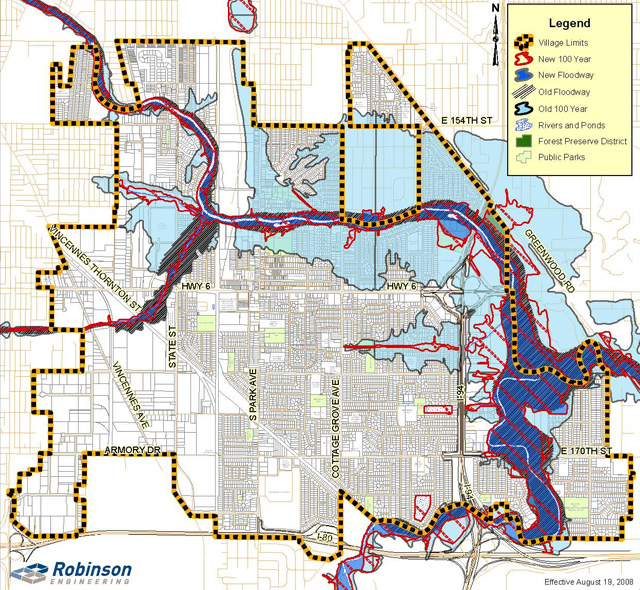

The overbank flood problems areas are shown on the floodplain map.

Floodplain Map

The map below shows the 100-year floodplain or Special Flood Hazard Area for South Holland as shown on the official Flood Insurance Rate Map for Cook County. It should not be used for any official determinations, such as insurance rate setting.

To find out if your property is in the official floodplain mapped on FEMA’s Flood Insurance Rate Map, contact the Planning and Development Department at 210-2915.

The Flood Insurance Rate Map was updated in August 2008. The new map shows a smaller Special Flood Hazard Area.

To see more flood maps in Illinois, visit http://www.illinoisfloodmaps.org.

For more information on FEMA’s maps, see http://www.fema.gov/information-homeowners

Click here for a larger version of this map (PDF – 1.95MB)

Little Calumet River Flood Levels

Flood heights have been recorded since 1947 on a river gauge that is currently located at the Cottage Grove Avenue bridge over the Little Calumet River. Recorded flood heights can be shown in stage or in elevation. Stage is measured in feet above an arbitrary starting point that was set when the gage was first installed. Elevations are in feet above sea level. Stage of zero on this gauge is the same as an elevation of 575.0 feet above sea level.

“Flood stage” is the elevation where the rising river stars to damage property. Yards and parks are flooded when the river reaches an elevation of approximately 590 feet above sea level. Buildings are affected at approximately 593 feet.

Using the 2000 Cook County Flood Insurance Study, the 10-year flood at Cottage Grove would reach a stage of 19.4 and an elevation of 594.4. The 100-year flood figures are 23.0 and 598.0.

In 2005, the National Weather Service issued a new “flood stage” level − 16.5 feet or an elevation of 591.5.

The Weather Service also provides real time stage data for the upstream river gauges on the Little Calumet River at South Holland, and on Thorn Creek at Thornton.

| Stage | Elevation | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 26.5 | 601.5 | 500-Year Flood |

| 23.0 | 598.0 | 100-Year Flood |

| 22.0 | 597.0 | 50-Year Flood |

| 20.8 | 595.8 | November 27, 1990 |

| 20.2 | 595.2 | June 14, 1981 |

| 20.1 | 595.1 | July 14, 1957 |

| 20.0 | 595.0 | July 20, 1996 |

| 19.6 | 594.6 | December 3, 1982 |

| 19.4 | 594.4 | 10-Year Flood |

| 19.2 | 594.2 | April 6, 1947 |

| 19.1 | 594.1 | February 21, 1997 |

| 19.0 | 594.0 | Water reaches buildings on Drexel |

| 18.6 | 593.6 | June 2, 1989 |

| 18.2 | 593.2 | October 10, 1954 |

| 18.0 | 593.0 | Thorn Creek begins to cover 170th Street |

| 17.9 | 592.9 | February 24, 1985 Water covers streets at Riverview and Drexel |

| 17.7 | 592.7 | December 27, 1965 |

| 17.0 | 592.0 | Flood Warning issued |

| 16.5 | 591.5 | National Weather Service Flood Stage |

| 16.0 | 591.0 | Flood Watch starts |

| 15.0 | 590.0 | Water enters Veterans Park |

Drainage problems

Flooding can also occur in streets when rainwater can’t flow into a storm sewer. Basements can flood when rainwater can’t flow away from the house or when the sewers back up. These problems are usually caused by heavy local rains and are often not related to overbank flooding or floodplain locations.

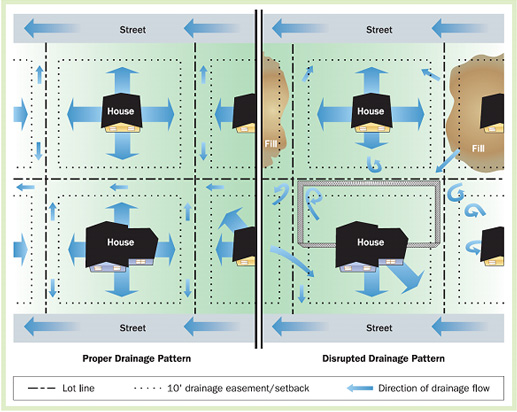

When an area is laid out for development, strips along the lot lines are set aside to carry water. Usually a five or ten foot easement is established. When the lot is built on, there should be no construction in the easement.

Filling on the lot should slope to the easement so drainage will run away from the building. A shallow depression or swale is kept along the lot lines. The swale guides stormwater runoff to the front or back yards where it is sent to the street or the storm sewer. Downspouts and sump pump discharge pipes should point to the swale so excess water is drained properly.

Over the years, this yard drainage system has been disrupted (see graphic). Many property owners are not aware of the need to keep their easements and swales open. They install sheds, planters, railroad ties or swimming pools in the easements. They build fences on their lot lines to enclose the largest part of their properties. As a result, the water stands in the yards because it cannot go anywhere. Eventually it percolates into the ground.

Sewer backup

Too much stormwater can overload a sewer. With no place to go, sewers back up and flow into the lowest opening in the sewer line. The graphic below shows that sanitary sewers back up into basements and storm sewers back up into streets.

Most of South Holland is served by separate storm and sanitary sewers, as shown below. Storm sewers are supposed to take stormwater. Too much stormwater backing up into the streets is a nuisance, but not a major problem. Sanitary sewers are not supposed to take stormwater. Increased flows in sanitary sewers increase the cost of treatment. Overloaded sanitary sewers backing up into basements are a major problem in property damage and health hazards.

Stormwater enters sanitary sewers through cracks in the pipes or manholes, deteriorating pipes and joints, breaks in nearby storm sewers, cross connections to storm sewers, and direct connections to downspouts, sump pumps, and driveway drains. “Infiltration” is groundwater entering the sewers through cracks. “Inflow” is stormwater directly entering the sanitary sewers from other sources. Infiltration and inflow (“I/I”) results in flooded basements in those areas served by separate sewers.

The older parts of South Holland are served by combined storm and sanitary sewer mains. Stormwater is supposed to enter the combined sewers. However, these can be overloaded also. With the Deep Tunnel project, the combined sewers are better able to handle their wet weather flows.